Ductography

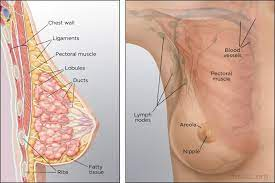

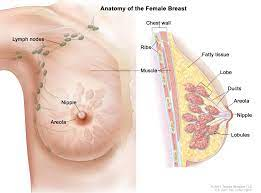

Anatomy of Breast

The breast is an organ that is unique to mammals and which has numerous important functions. In female humans, the breasts have an additional aesthetic and erotic role. This article will provide an in-depth overview of the anatomy of the female human breast. Key topics covered include breast structure and tissue composition, the nipple and areola complex, blood and nerve supply, lymphatic drainage, changes across the life cycle from puberty through pregnancy, lactation and menopause, anatomical variations, and clinical correlations of anatomical features with breast pathology.

External Structure and Shape

The breasts overlay the pectoralis major muscles of the chest wall and extend from the level of the second rib to the sixth rib in the vertical dimension. Each breast contains a nipple surrounded by a pigmented circular area called the areola. The size and shape of breasts vary widely, with size and shape determined by the interaction of genetic and environmental factors. Influences include body weight, parity, age, medication use and endocrine disorders. Many classifications have been made according to size and shape including clinician-derived systems and self-reported categorizations. These have clinical value in surgical planning and self-image understanding.

Internal Structure and Tissue Composition

The breast contains no muscle tissue and consists entirely of connective and epithelial tissues which provide structure, and adipose tissue which accounts for volume. There are 15-20 irregular lobes within each breast consisting of milk glands, milk ducts, fat and connective tissue. The milk duct system is a branching network of ducts which carry milk from the lobes to the nipple. The proportions of glandular, connective and adipose tissue vary between individuals and account for density differences apparent by palpation or mammography. Greater glandular and connective tissue increases density, while greater adipose tissue reduces density and imparts more compressibility.

Blood and Nerve Supply

The arterial blood supply to the breast derives from perforating branches off the internal mammary artery (medially), lateral thoracic artery (laterally) and 2nd to 6th intercostal perforating branches of the internal thoracic artery (inferiorly). There is free anastomosis between these vessels.

Venous drainage mirrors arteries. Nerve supply is from anterior and lateral cutaneous branches of 4th to 6th intercostal nerves.

Lymphatic Drainage

Lymphatics from the breast tissue converge to form collecting trunks that lead to axillary lymph nodes. About 75% of lymph from the breast drains to the axillary nodes, while 25% drains to parasternal nodes. Most lymphatic flow is to the ipsilateral axilla, but up to 10% may cross to the opposite axilla. Axillary nodes are clinically important because breast cancer typically metastasizes first here. The axillary nodes are divided into levels based on anatomy - Level I being lower axilla, Level II mid and Level III upper.

Changes Across the Life Cycle

Key changes occur during distinct life phases under the influence of hormones -

Puberty

- Estrogen stimulates fat deposition and causes breast bud formation

- Duct system develops and extends

Menstruation/Reproductive

- Cyclical changes across menstrual cycle reflecting hormone levels

- Pregnancy causes enlargement and preparation for lactation

- Post-lactation involution and potential lasting volume changes

Menopause

- Decreased estrogen levels lead to atrophy of glandular tissue and regression

Anatomical Variations

Many variations in shape, size, symmetry and position occur, most are normal variants rather than pathologic. Some examples include:

- Additional nipples (polythelia)

- Accessory breast tissue (polymastia)

- Webbing of skin between breasts (synmastia)

- Nipple inversion

- Tuberous breast deformity

- Ptosis - drooping breast

- Hypoplasia/aplasia - underdeveloped breast

Clinical Correlations with Breast Pathology

Many breast diseases manifest through palpable findings in breast anatomy before being visible on imaging. Understanding key relations aids clinical detection and diagnosis. Some key examples:

- Cancer often forms in terminal duct lobular units near nipple

- Abscess formation guided by tissue planes between lobules

- Fat necrosis along blood supply routes

- Cyclical pain tied to hormone effects on breast tissue

This overview covers key aspects of the intricate anatomy of the female human breast including the structure, tissue composition, vasculature, innervation, lymphatic drainage and anatomical changes across the lifecycle. An understanding of anatomy facilitates early diagnosis of pathology. Additional detail on embryological origins of breast development, molecular factors and histology exists but is beyond the scope here. In summary, the breast is a truly intricate organ that uniquely varies in form and function across individuals.

Ductography

Ductography, or galactography, is an imaging procedure used to evaluate pathologic nipple discharge from the breast. It involves cannulating and injecting contrast material into the discharging ducts, followed by mammographic imaging to visualize the duct anatomy. Ductography helps identify intraductal lesions that may cause abnormal nipple discharge.

Indications

The

main indications for ductography include:

- Unilateral spontaneous single-duct

serous or bloody nipple discharge in women over age 40. This raises concerns

for papilloma or ductal carcinoma.

- Evaluating the extent of known

papillomas or ductal tumours causing discharge.

- Assessing surgical results following

excision of intraductal lesions.

- Localizing the source of discharge

when ultrasound and diagnostic mammograms are unrevealing.

- Determining which ducts are involved

when multiple sites of discharge are present.

- Ductography is an important diagnostic tool for further evaluating pathological nipple discharge, often warranting surgical excision.

Contraindications

Ductography

should be avoided in patients with:

- Active breast infection or abscess.

- Severe contrast allergy.

- Marked nipple retraction or scarring

obstructing duct access.

- Extensive breast malignancy or

radiation therapy resulting in ductal distortion.

Patient Preparation

Before

ductography:

- Obtain informed consent after

explaining the risks.

- Confirm no lactation, pregnancy or

active infection.

- Clean the nipple region with

antiseptic.

- Perform breast examination to assess

for masses.

- Prepare equipment including

magnification device, catheter, and water-soluble contrast.

Catheterization Technique

The patient is seated or recumbent during the

procedure.

- The discharging duct opening is

cannulated using a blunt-tip catheter.

- Low-pressure hand injection introduces

the radiographic contrast.

- Magnification ensures proper

cannulation and documents successful filling.

- Mammographic views localize filled

ducts and assess for filling defects.

- Ducts may be imaged while

compressing the breast to evaluate intraductal lesions.

Interpretation

The

images are assessed for:

- The extent of ductography and which

ducts fill.

- Filling defects within opacified

ducts indicate intraluminal masses.

- Extravasation and ductal

perforation.

- Nipple involvement or associated

masses.

- Specimen radiography is performed on excised intraductal lesions to confirm successful removal.

Complications

- Potential complications of ductography include:

- Mastitis or abscess formation if

inadequate antiseptic technique is used.

- Intraductal contrast extravasation

due to high-pressure injection or perforation.

- Difficulty accessing and cannulating

certain ducts.

- Inability to identify the source of

discharge if multiple openings are present.

- Proper sterile technique minimizes risks like infection and inflammation.

Ductography

is a specialized mammographic technique to reveal intraductal breast lesions

causing nipple discharge. Understanding appropriate patient selection,

cannulation methods, and image interpretation can provide valuable diagnostic

information to guide surgical management when standard imaging is

nondiagnostic.